Baggy Mythbusters Episode 2: Shares vs. "Shares"

Let's blow a few minds, shall we?

"He who sells what isn't his'n, must buy it back or go to pris'n." - Daniel Drew

Just over three years ago I wrote about the pandemic of investors misinterpreting FINRA’s daily short volume data and using it to wrongly conclude that directional short selling accounts for a massive amount of volume across all securities. You can read it here:

Baggy Mythbusters Episode 1: Misunderstood and Misused - "Daily Short Volume"

“The truth is more important than the facts” - Frank Lloyd Wright How many times have you seen something like the below exchange play out on social media (e.g. Twitter or its lowbrow bastard child Stocktwits)? If I had a Dogecoin for every time I read a post about “daily short volume”, I’d have a lot of worthless Dogecoin. While it would be easy (and q…

Or even better, rather than reading that drivel, go to the FINRA website and read their document with the confusing title “Understanding Short Sale Volume Data”

https://www.finra.org/rules-guidance/notices/information-notice-051019

It’s clear that efforts to educate people on such matters have been highly successful. If you don’t believe me, just search “741” and “$DJT” on X (formerly Twitter): $DJT and 741.

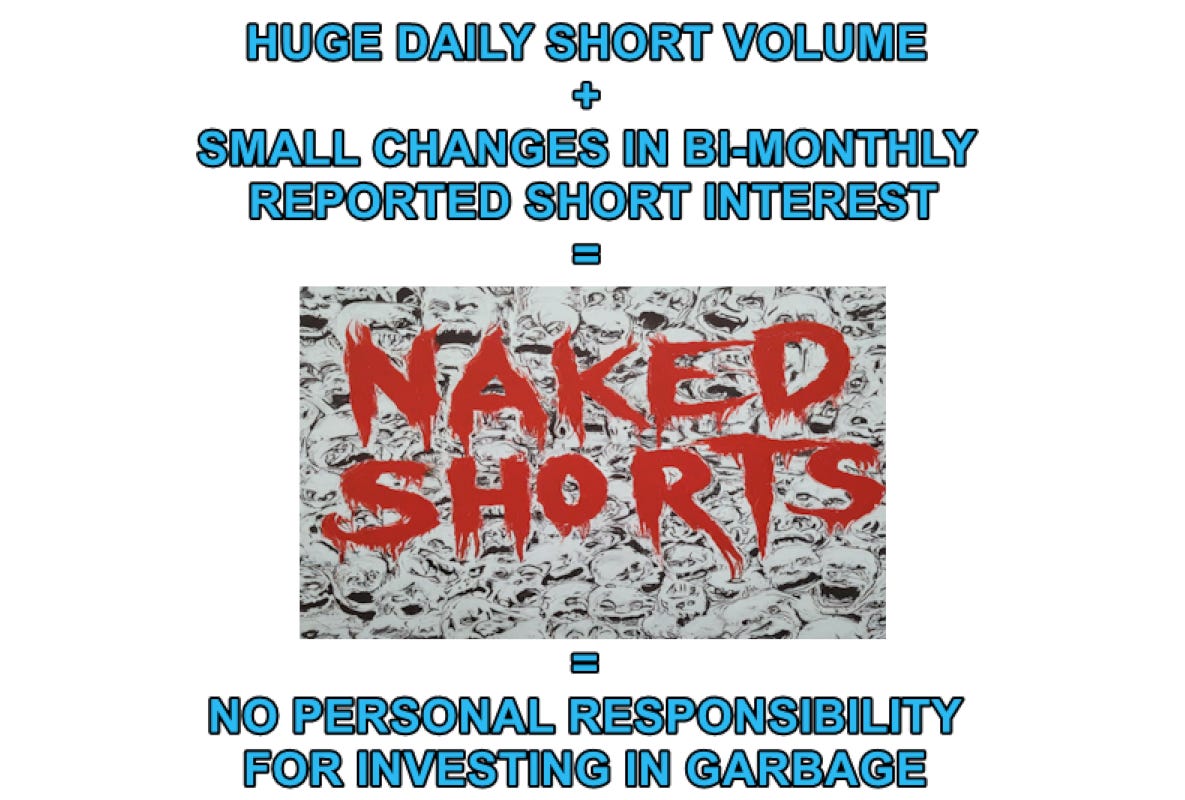

More seriously, I believe the misinterpretation of the above data, and its questionable use by questionable human beings, is a major reason retail investors are getting ripped off daily in financial markets. The sassy image below pretty much sums up the “logic”:

Given the apparent success in educating some people about daily short volume, I thought it might be helpful to clear up another matter that’s been irking me. How often have you seen posts like these on social media?

Source: X (and May the fourth be with this baggie)

Source: X

Intuitively, these reincarnated Charlie Mungers have a point, right? How do you sell something you don’t even own? If I lend my car to a neighbor and he sells it to someone, that’s fraud! Right? If I loan my shares to a short seller and she sells them to another investor, how does that buyer then own my shares? Counterfeit shares! Fraud I says! Right?

If you’re nodding in violent agreement with the above paragraph, there’s a 99% chance you are too far gone and should just stop reading now. But on the slim chance you’re one of the 1% that is open to some facts, then keep reading.

Lean in.

Listen close.

Take a deep breath.

Open your mind.

Unlike loaning your car to a friend, when you or your broker lends out your shares, at at that point:

The man with a belt, suspenders, and an impossibly-high second shirt button is right. Once those shares are “lent”, you no longer have legal title (whether directly, or indirectly if held in street name), nor are you the beneficial owner of those shares. I know what some (most? hopefully not all) are thinking right now:

If those shares are lent to a short seller (grrrrr), and that short seller sells them in the market, the buyer of those shares owns them. Legally and beneficially. Free and clear. No scarlet letter showing them as “fake”, “shorted”, “counterfeit”, or whatever. That investor gets to vote the shares. That investor gets the dividends from the company. That investor can even lend them out to new short sellers. This latter point is one of the reasons why short interest can theoretically be higher than the float or even total outstanding shares (but perhaps that’s for a future Baggy Mythbusters episode).

So while you don’t own those shares that were lent out, you do have a *position* in that security. Specifically, you have:

The right to receive shares back at the end of the loan period (if, for example, you recall those shares, or the short seller decides to return them).

Payment in lieu of dividends. If the company pays a cash dividend to the actual shareholders (not you, as you don’t own them), the short seller is required to pay you an equivalent amount).

Any non-cash distributions at the end of the loan period.

Sometimes, a lending fee that the broker may or may not share with you, depending on the circumstances.

In addition your broker will, in all likelihood, be holding collateral from the short seller.

(Note: the above is for a typical share lending arrangement. Agreements can vary between brokers or even individual clients - consult your actual broker or financial advisor)

While called a “loan”, it’s actually a bit of a misnomer, given legal and beneficial ownership has actually been transferred. But it is a “loan” in the sense that you are owed something.

Similarly, “shares” (once lent out) is a bit of a misnomer, as you actually don’t have that legal and beneficial ownership. You have a position, and retain economic interest in the underlying stock. It’s understandable that most people use the word “shares” to reflect their account holdings, but these are important distinctions to understand if our brains are to keep from turning into mashed potatoes with nutty conspiracy theories.

One question that comes up occasionally is why, if legal and beneficial title is relinquished, it doesn’t trigger capital gains for tax purposes. I’ll let Google Gemini handle this one:

Source: Google Gemini Advanced (consult your own tax advisor)

A simple example may help illustrate what’s going on. Consider:

Investor A owns 100 shares in a margin account (or chooses to participate in a share lending program) on Day 1.

On Day 2, a clothed short seller arranges, through the broker(s), to borrow 50 of Investor A’s shares, but does not sell them on Day 2 (perhaps the FUD isn’t quite ready to go?).

On Day 3, The short seller sells those 50 borrowed shares in the market to Investor B.

The table below shows what is happening here:

This is of course very simple for illustrative purposes. Actual mechanics can be more complex. However, in our example you can see that the share count (actual shares) never changes, but the number of long positions does change. You’ll also observe that the net long position across all three parties does not change, and is always equal to the share count.

If the above were a real-world example and accounted for all of a company’s securities, you’d be hearing howls about how investors own 150 shares but there are only 100 shares outstanding, and how thus there are 50 “fake” or “counterfeit” shares.

That’s not to say that it’s impossible for shenanigans and tomfoolery to exist with respect to short selling. For example, the SEC recently laid charges in an “abusive naked short selling scheme” (Link: https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2023-107). Good. The point I’m trying to make here is that one (there are several) of the pillars of the “counterfeit shares” conspiracy theories (e.g. spouted for years by AMC investors) is born from a lack of basic understanding of what a stock loan actually is, and the difference between a share and a “share”.

“There are two times in a man's life when he should not speculate: when he can't afford it, and when he can.” - Mark Twain

Bravo! I was hoping $DJT would bring you back to the land of the posting.

Thanks, that's a very clear explanation! I came across this theme when buying GME back in 2020, never fully understood it.