Baggy Mythbusters Episode 4: sEcuRiTeS sOLd nOt yEt pUrcHaSeD

The mundane market maker balance sheet item making some investors go bananas

This is part 4 in an ongoing series intended to educate (and totally not mock) the ignorami about various tropes they circulate to explain why their massive and ongoing investment losses are always someone else’s fault.

I have mixed feelings about this particular topic. On the one hand, I legitimately applaud the attempt by some of these people to “do their DD” by cracking SEC filings and at least trying to understand something. On the other hand, most (all?) of these people have already drawn their firm conclusions are just looking for red meat to feed their confirmation bias. As an aside, after writing that sentence I wondered how an AI image generator would depict this:

Source: “Ignorami reading SEC filings looking for red meat to feed their confirmation bias” - as depicted by Microsoft Copilot Designer AI

Market making firms have long been the target of scalded bagholders. Despite being able to execute trades at very tight bid/ask spreads, for extremely low (and often zero) commissions, the irked masses are still convinced that prices themselves are being manipulated by market makers and driving equity prices invariably lower.

The onslaught against the large market making firms such as Citadel Securities and Virtu has picked up in recent years following the “meme stock” frenzy of 2021, and its brief resurgence this week.

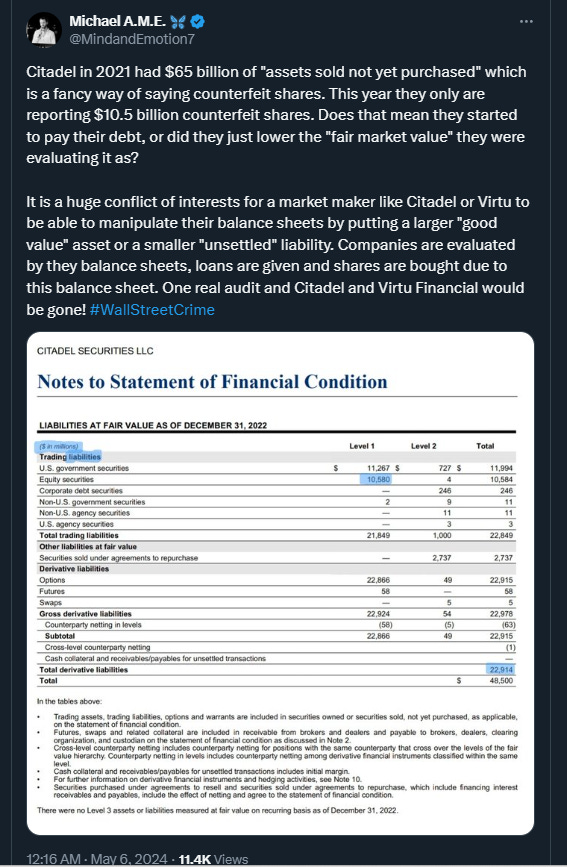

Over the past year or so, they have latched on to one item in particular on the balance sheets of market making firms: “Securities sold, not yet purchased”. Take this gentleman’s tirade, for example (the first that popped up in my search):

Source: https://x.com/MindandEmotion7/status/1787335513667453024

Let’s ignore for a moment that he conflates assets with liabilities, is comparing a $65B total securities liability in 2021 to just the $10.5B equity securities liability in 2022 (the same line item was actually $13.98B in 2011). Focus on the angst and rage. Counterfeit shares! Cooking the books! #WallStreetCrime !!!!! Argggh!!!

Before we look at some numbers, it’s worthwhile to take a step back and remind ourselves, in very simple terms, what these firms do. Market makers facilitate trading, and provide liquidity. In essence, these firms are always ready to buy or sell a security, even if there are no other buyers or sellers in the market at a particular moment.

By continuously quoting bid and ask prices, temporary imbalances between supply and demand are absorbed, resulting in reduced price volatility, increased liquidity (particularly for the small investors that teabag these firms nonstop on social media), and narrower bid-ask spreads (due to competition from fellow market makers).

Perhaps you are a fan of flash crashes, insane price swings, getting blown out of positions with margin calls on intraday volatility because some clown at Fidelity fat fingered a trade on your shitco small cap. If so then perhaps you don’t want market makers to exist. Fine. For our purposes here though, the pros and cons of the existence of market makers don’t really matter.

What does matter is the fact that the vast majority of market makers make money on capturing bid/ask spread. In short, [Bid/ask spread] X [Volume] = Market Maker Profit.

Market making is not about taking directional bets. Read that sentence a few times. There are actually, believe it or not, rules and regulations that limit this activity. Banks were more or less booted out of the game with the Volcker Rule, but market making firms such as Citadel and Virtu are not only highly-regulated, but are subject to contracts known as “Market Maker Agreements” with exchanges such as the NYSE and NASDAQ. The NYSE, for example, has specific rules for what designated market makers can and cannot do. For example, see Rule 104 here:

https://nyseguide.srorules.com/rules/negg0130d5b3b47b0710008b8f00215ad78774045?searchId=2309536936

Now let’s do a bit of math, assuming you don’t believe anything I wrote above, that “they” are all a “bunch of crooks” and the Citadels of the world are free to manipulate all of your totally high-quality stocks into the ground. Citadel’s audited financial statements for the year ended December 31, 2023 are found below:

https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1146184/000114618424000001/CDRG_BS_Only_2023.pdf

In the notes we can see that equity securities sold short totals about $11.4 Billion.

Now let’s assume that Citadel uses NONE of that capital for market making, and it is all just allocated to the market manipulation department 200 floors below the surface of their headquarters. Let’s put that $11.4 Billion into context. A broad stock market index, the FT Wilshire 5000 Full Cap index, essentially the full market capitalization of the U.S. equity market, is worth $52.3 Trillion (with a T). Citadel, by far the largest equity market maker, has an entire short equity book equivalent to 0.0217% of the Wilshire 5000. And that’s just for U.S. equities. Citadel makes markets in 35 countries including Japan and small places like Europe.

To put that 0.0217% in context. Go stand next to the 1,454 foot tall Empire State Building. 0.0217% of that height is less than 4 inches. About as far off the sidewalk as your hands droop down from carrying all of those bags, amirite.

Daily equity trading volume and value is enormous. According to the CBOE, the average daily equity value for the past five days was $526 Billion per day. In 2023, 23% of U.S. equity market volume was executed through Citadel Securities. Assuming volume share is a proxy for value share, it’s reasonable to conclude that Citadel is routinely trading over $100 Billion in U.S. equities per day. $15 Billion or so per trading hour. Plus trading in over 34 other countries.

The point I’m making here is that if you think Citadel, as the largest market maker, is “manipulating” prices on in a directional manner, on a systemic and material basis, they are going to need a LOT more capital to do so.

So why are market makers short any equities at all?

Normal course market making

By providing constant bids and asks on equities, there will be times when a market maker may be long a security at the end of a trading day (including at quarter and year-end financial statement dates), particularly in securities that don’t trade every millisecond, second, or minute, and where net sellers may be more active than net buyers. Thus it’s not surprising that as at December 31, 2023, Citadel Securities was long $18.2 Billion in equity securities:

Source: Citadel SEC Filings

Conversely, this would be true on the short side as well. If net buyers are greater than net sellers, it’s possible that at the end of a trading day a market maker would be short some securities.

It’s worth noting here that Citadel’s $18.2B long equities position is greater than its $11.4B equity short positions. At least as at December 31, 2023, all else being equal, Citadel’s balance sheet was net long equities, in aggregate.

It’s also worth noting that these are aggregate figures. With out access to the company’s trading records one can’t definitively prove that a particular security hasn’t been “manipulated” or subject to tomfoolery, but by looking at aggregate data it’s hard to conclude there’s a systemic or market-wide issue.

Hedging

Arguably far more important to understanding a market maker balance sheet is a reminder that market makers are in the business of capturing bid ask spread, and as such are extensive hedgers. This may involve taking offsetting long or short positions in individual equities or index products to offset certain exposures.

Citadel’s balance sheet also shows us perhaps the greatest reason why they have such large equity long and short exposure: options.

Citadel is one of the largest, if not the largest, options market makers as well. As at December 31, 2023, Citadel had $35.1 Billion in Options assets on its books, and $36.8 Billion in Options liabilities (see balance sheet items posted above).

Option contracts tend to be far less liquid than their underlying securities, and as such the bid/ask spreads tend to be wider. These wide spreads are catnip for market makers, especially as the exposure can be easily hedged out.

Market makers engage in “delta hedging” when they take the other side of an option trade. I won’t get into the mechanics too much here but “delta” is, in essence, how much an option price changes compared to a change in price of the underlying security. For example, with Alphabet trading at around $175, a call option with a $100 strike price will have a high delta, meaning if Alphabet goes to $180, the call option price will increase nearly $5 as well. Delta can range from -1 (negative for put options) and +1 (positive for call options).

Let’s use a simple live example. Assume you licked a few too many psychedelic toads and a leprechaun told you that GME 0.00%↑ is going to $60 dollars at the end of May. You do the only logical thing and take your child’s college fund and your parents’ IRA and put it all into May 31 $50 strike call options.

Source: Toad venom-induced hysteria

You see that the call options, soon to be worth $10, have a bid of $0.27 and an ask of $0.37, with a last price of $0.30. You smartly put in a market order for 1,000 contracts, representing 100,000 shares (each contract = 100 shares). Given the guaranteed nature of this bet, there is nobody dumb enough to take the other side of this trade. That’s where the beauty of having market makers come in. The market maker takes the other side of that bet and sells you the call options at $0.37, the ask price.

You’ve spent $37,000 and, unless that leprechaun lied to you, it will turn into $1 million in just a few days. But the market maker doesn’t want to lose $963K ($1M less the college fund and parents life savings you forked over), so what does it do?

It hedges. The “delta” of those call options is low, at 0.08. That means if GME, trading for around $19, goes to $20, the call options could be expected to increase in value by $0.08. To hedge the risk, the market maker will buy 8,000 GME (0.08 x 100,000), so what it loses on its short call option position, it makes an offsetting profit on its long equity position.

The inverse happens with put contracts, where a market maker that sells you a put option will short enough of the underlying shares in the market to remain roughly “delta neutral”. These long and short hedges will be adjusted, increased, decreased, and unwound continuously based on aggregate exposure.

In our simple example above, the market maker’s ideal scenario would be for someone to come along soon and want to sell 1,000 contracts (e.g. a dumb bear, or perhaps a long that wants to write a covered call option), so the market maker fills the order at $0.27, unwinds its delta hedging, walks away with $10,000 profit that it can use to pay bashers on Reddit or bribe Congress, I guess.

The key point here is it would be very unusual for option market makers NOT to have a sizeable equity long and short book in order to hedge their exposures and manage risk. Significant options assets and liabilities, like those on Citadel’s books, will naturally result in significant long and short equity positions.

Final note: Please don’t take the leprechaun’s advice here. It was just for illustrative purposes. But if you must, and it doesn’t work out, make sure you blame everyone but yourself for why it didn’t work out. If you choose to blame “the MMs”, however, don’t use their audited, SEC-filed balance sheets as proof their chicanery.

“It is far easier to blame others for your misfortunes than to search your soul for the cause.” - Socrates

kek baggies

the funny thing is the real scam is right in front of everyone's face and no one seems to care - mind share of possible investment ideas via sell side analysts with the megaphone of the financial media, as well as buy side investors talking their book.